[00:00:00]

Deana: Welcome to Stories for Power. I’m Deana Lewis and I’m a member of Just Practice Collaborative. Stories For Power is an oral history project produced by Just Practice Collaborative and Creative Interventions. It explores the political lineage and historical experiments that gave way to this wave of transformative justice, community accountability, and prison abolition.

In each episode of Stories for Power, we speak with activists and organizers from different cities who were and continue to be at the forefront of feminist abolitionist praxis. They talk about the bold experiments and interventions they were a part of in the early 2000s through 2010, and how their work informed abolitionists transformative justice and community accountability organizing today.

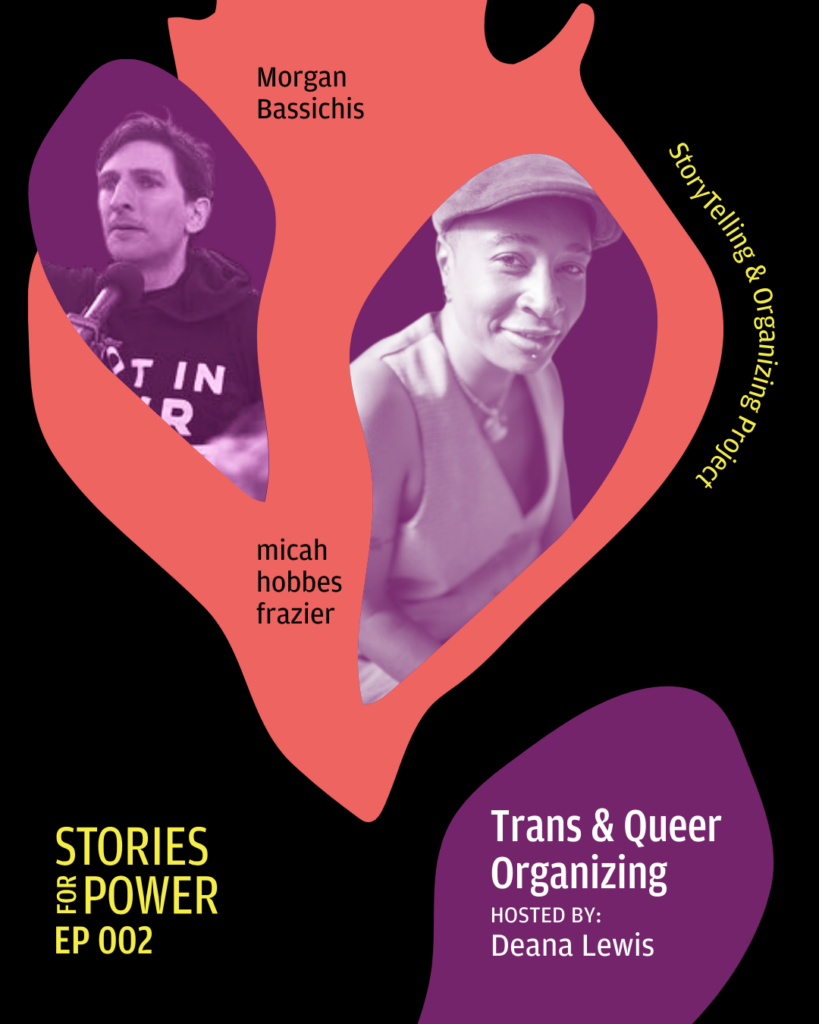

Don’t worry, if any terms or words have you confused we’ll do our [00:01:00] best to link to resources in the show notes, and you can always go back to listen to the special introduction episode for more context. In this episode, you will hear from two inspiring abolitionist feminists, Micah Hobbes Frazier and Morgan Bassichis.

We will talk about the courageous and radical work they were part of between the early 2000s and 2010.

Have you facilitated a process using community accountability tools or strategies? We want to hear your stories. Creative Interventions and Just Practice Collaborative wanna share new stories from people who are taking action to end interpersonal violence without the use of police or carceral systems.

Find the link in our show notes to learn more.

A note for our listeners, we’ll be discussing violence, including police violence, intimate partner violence, and community violence. We encourage you to take care of yourself, and we understand that taking care of yourself can also look like not listening to this [00:02:00] podcast until you’re ready.

A quick heads up, there might be a couple of audio issues in this episode. Now let me introduce our guests. They have amazing and extensive experiences and knowledge. I’ll do my best to summarize. We have linked their full bios in the show notes. You can also learn more on our website StoriesforPower.org.

Morgan Bassichis is a performer, writer, and artist living in New York City.

They’re the co-editor of Questions to Ask Before Your Bat Mitzvah, an accessible anti-Zionist anthology for people of all ages. While living in San Francisco, Morgan was a staff member at Community United Against Violence, also known as CUAV. They were also a volunteer with the Transgender Gender Variant Intersex Justice Project, also known as TGIJP.

They have been a member of Jewish Voice for Peace, New York City since 2014, which organizes Jews away from Zionism and towards collective [00:03:00] liberation and Palestinian freedom.

Morgan: So my name is Morgan Bassichis and um, I was a staff member at Community United Against Violence CUAV in San Francisco from 2007 to 2013.

And during that same period of time, I was a member of the Transgender Gender Variant Intersex Justice Project, TGIJP. And was also around that time involved in the planning of the Critical Resistance 10 conference in 2008 and an organization called Justice Now, which worked with people in women’s prison – so just in that mix of, kind of queer and trans prison abolition, transformative justice, imagination, practice, resistance and it was so formative to me in so many ways.

Deana: Micah Hobbs Frazier is a black queer two-spirit facilitator, somatic coach, body worker, doula, and magic maker living, loving, laughing, and building community in [00:04:00] Tulum, Mexico.

He deeply believes that personal healing must always be connected to collective liberation, and is the founder of the legendary Living Room Project, an accessible Healing Justice and community space for queer and trans people of color. Micah facilitates spaces to address conflict, harm, and violence, heal trauma and grief, and create sustainable practices that are aligned with principles, values, and vision.

Micah is an innovative and highly skilled facilitator with over 20 years of direct service and organizing experience. He has a commitment to facilitating spaces where healing and transformation are possible. Deeply rooted in healing, justice, harm reduction, and transformative justice principles and practices, Micah uses his skills and magic to break the cycles of trauma and violence in our families and communities.

Micah: So my name is Micah. I’m Micah Hobbs Frazier. I am a facilitator and somatic healer, a doula, sometimes DJ. [00:05:00] Then I was a staff person, program team member for generationFIVE, and our work was really about ending child sexual abuse in five generations, using transformative justice as a way to also change the systems, conditions, context in which, which allows for, for child sexual abuse to happen.

And through generationFIVE, we also were part of a few different collaboratives, organizations working together to forward transformative justice in multiple arenas. So working with CUAV, Critical Resistance, and also then bringing together folks from different parts of the country, like folks in Atlanta, folks in New York, to build transformative justice collaboratives in different parts of the country, to be able to forward transformative justice work in [00:06:00] other contexts and other locations – like racial justice, you know, men’s work, environmental justice, which we were calling it then, not climate justice, in schools, social work, you know, different places.

Deana: Thank you for that. I wanna talk a little bit about the context in your cities and communities that helped kick off your different projects.

And as you’re talking, can you please, you know, talk more about the queer and trans organizing in the SF Bay area at the time and how that may have influenced your work?

Morgan: The influence of queer and trans communities, leadership, politics, I think was so central in this moment. Certainly in the Bay Area, there felt like some excitement, where a kind of radical impulse that was centering racial justice and economic justice, and struggles against state violence. So many of us were saying this needs to be the center of any [00:07:00] LGBTQ queer trans agenda. Any agenda that is not centering issues of poverty and state violence and mass incarceration is not reflective of the agenda that our communities need and deserve. And so, it just felt like a lot of cross pollination and convergence between all these different struggles and collectives and collaboratives and organizations and places, trying to weave together abolition, the idea that we all need, deserve a world beyond prisons and police and walls and cages, with a need to reclaim queer and trans politics from some of the neoliberal, racist co-optations of those politics that were born out of struggles against police and state violence.

And so it felt like this moment of a lot of queer and trans activists reclaiming queer and trans politics from an agenda that had been, in some ways, dominated [00:08:00] by pretty conservative priorities like marriage, and inclusion in the military, and hate crimes laws. And there felt like a major pushback to that conservative agenda that said, “we wanna center grassroots struggles that dismantle white supremacy, and capitalism, and state violence.”

And so, I had the real honor of getting to, to join this organization, CUAV, Community United Against Violence, which has been around since 1979 as one of the country’s first LGBTQ anti-violence organizations – came out of the, the White Night riots in San Francisco after the assassination of Harvey Milk.

And it had gone through, like so many queer and trans organizations, a whole political journey in which it started as this grassroots group, and then had many different iterations and incarnations. And many of those iterations were shaped by the state and state funding and the kind of funding streams that open up and say, this is what anti-violence [00:09:00] work means.

This is who you work with, this is the frame, and this is what a, a kind of service model that kind of comes in to supplant other more creative grassroots models. And so I got to be there in the organization during a really exciting time when we were reconceptualizing what our approach was as an organization. And in some ways, returning to some of those earlier grassroots strategies and saying, we want to not just be able to replicate this kind of service provider model, which often relies on police and policing to address hate violence, domestic violence, sexual violence, and we wanna be part of this creative internationalist efforts to reclaim anti-violence work. And to reject the idea that hate crimes laws, which mean more cops on the street and longer prison sentences, translates to safety for queer and trans people, when we know what that translates to is more warehousing of poor, Black and brown people. So we say no to that. [00:10:00] And we say yes to this demand to figure out another way. And last thing I’ll say is the efforts to support queer and trans people who are locked up and coming out of jail and prison, and efforts to create transformative solutions to violence that don’t rely on the police were always connected. They were never separate. Like it was always, always interwoven, both abolition and transformative justice, like, same people thinking about the same things.

Micah: I love listening to you, Morgan, and you know, and just like remembering, right?

It like brings me back to those times and I, I think some of the things that I would add is, is like even though the leadership of the work was queer and trans, there was like this kind of intentional reframing of our work. And I think part of that became really about looking at okay, but who’s most impacted? And how can we center the folks that are most impacted? [00:11:00]

And when we looked at that, all of the different work that we were doing, whether it was racial justice, economic justice, you know, ending child sexual abuse, prison abolition, you know, what we, I don’t even wanna say discovered, because it’s something that we already knew, but I think had to return back to – is that it’s, it’s queer and trans folks, and particularly BIPOC queer and trans folks who are most impacted by this. And so I think that really helped us also to guide our work. The most interesting [thing] about that is that it also reflected the leadership that we were in and also growing as well. And so it was kind of also this natural flow of like reclaiming leadership in those places that often BIPOC queer and trans leadership was not really being supported or put forward, and then all of a sudden there was this huge, you know, contingent of BIPOC queer and [00:12:00] trans leadership really leading this work. Child sexual abuse work in particular, has been really centered and connected to domestic violence work, which often was very like white, cis woman based.

And for us to be able to kind of turn that around and really center it around BIPOC queer and trans folks and really looking at, no, you know, these laws that you’re trying to pass in these areas and the focus on stranger danger and, you know, all these things actually don’t reflect what’s happening in reality and happening on the ground. And the impacts that these laws actually then have on our people.

There was a lot of focus at that time on sex offender registry laws, as well, which, you know, a huge focus. And, you know, how can we pass these sex offender registry laws, which, you know, are really just [00:13:00] about criminalizing folks more and not actually about healing and restoration and accountability.

And the other understanding that we came to is like what we know is that criminalization and locking people up and throwing them away doesn’t work, right? It actually doesn’t work for the kind of rehabilitation, restitution, repair, healing, and accountability. And the transformation that we actually want for our people who have done harm and our communities who have experienced harm.

And so, you know, we need to focus on other things. And, you know, I think also there was a part of us that was like, okay, as queer and trans folks, we have this long history of creativity and healing in our communities, and particularly as BIPOC queer and trans folks, you know, we also have this long history and tradition and practices of restorative justice [00:14:00] and healing and accountability through connection.

And so how can we draw on those things to really be the kind of focus and drivers of our work? And, you know, it was super exciting to be in those moments and those times, and then see the collaborations and experience the collaborations that came out of all of that.

I think the last thing that I’ll add to this is you asked us to talk a little bit about the San Francisco Bay Area, and what’s interesting is even just talking about it as the San Francisco Bay Area, right, like center San Francisco in this way, that I think is not actually reflective of a lot of what was happening at the time. You know, but just is kind of in keeping with how San Francisco often gets like, centered, right? – as like the base of activity, the base of any kind of radical work.

And, and actually, you know, although yes, a lot of work was based in San Francisco, there was a lot of work that was actually based in Oakland. [00:15:00] Right? And Black Oakland, you know, really coming forward to take its place in this work and to really show that we have leadership, we have creativity, we have history to draw on, including, as we all know, the Black Panthers. And to really bring forward the history and power and leadership that Oakland also had to offer, instead of just centering it on San Francisco, which is very much tied to white gay men. And that’s not what our movements, our work was centering or wanting to center.

Deana: Thank you for that. Can you tell me more also about what you were specifically responding to in your organizations? You both mentioned legislation, but were there other things that were happening that made you and your organization take a turn and say, oh no, we’re focusing on community accountability and transformative justice? And even if [00:16:00] you didn’t use those terms back then, what terms were you using?

Morgan: Well, I’ve actually been thinking about that time because Kamala Harris was the San Francisco District Attorney at that moment, and one of her big platforms was to remove what was called the Gay and Trans Panic Defense as a kind of defense strategy around hate violence.

And often we as CUAV were called for any effort that makes prosecution look queer and trans friendly. And, you know, there’s a whole kind of history to the integration of data collection around violence – its kind of usage by the criminal legal system. During that time, one of her big focuses was on saying that the DA’s office stands for queer and trans safety or something, and we were kind of outraged by that co-optation – and that divide and conquer strategy built in there saying that the criminal legal system could ever be an ally to queer and trans communities. That immediately [00:17:00] says, which queer and trans people are you talking about? And immediately throws so many people under the bus, specifically BIPOC queer and trans people, and BIPOC people in general. Yeah, the idea that prisons and police could ever be an ally of queer and trans people is such a white fantasy and delusion, which even in that is questionable.

You know, like the level of indoctrination that so many of us have received that incarceration and prosecution equals healing or equals repair or equals justice. And the level of internalization that has happened. I forget which year, but Obama signed this national hate crimes legislation and so we were also responding to that.

There was a lot of us that were going against the tide of what we were seeing both in like national LGBT politics as well as in like some of the larger anti domestic violence formations, which have many radical people and radical histories, but they often kind of don’t surface to the top and don’t become the frame. And also, it both felt like there was a lot of us and also a lonelier period. [00:18:00]

What other events were we responding to? I would say we were really inspired by the work of the Audre Lorde Project and Safe Outside the System in New York City. I remember we once did a little learning trip to New York where we went to go to one of SOS’s, Safe Outside the System’s Community Day, kind of mini convening they were having.

So these conversations were happening everywhere, around how racial justice needs to be centered in any queer and trans work. And also during that time, unfortunately and painfully, there were many queer and trans people who were murdered. And so we were constantly being faced with this question of how do we respond to murders in our community, particularly trans women of color, obviously with the highest rates of murder, of houselessness, of incarceration, of being deprived healthcare and affirming healthcare.

And so we were just constantly being confronted with how do we hold the balance of affirming the wishes and desires that someone’s family might have, and the wishes and desires that someone’s community might have. And when, when they might be in tension and when, [00:19:00] when they might be in alignment. And like Micah was saying, how do we look at the root causes and not just be in reactionary mode, and sort of just take on the state’s script and how they want to conscript us into their narrative.

And so, it was through having constantly to be confronted with these questions that we were like, we have to figure out another way. And we have to speak back and not let our work be a kind of subsidiary of the prison industrial complex.

Micah: I think one of the biggest things that we were responding to is this pathologizing of queerness and transness. That queer and trans folks are not safe. They’re not safe to be around our children. They are pedophiles inherently, and more likely to sexually abuse children. And for us as an organization, particularly focused on child sexual abuse, there was a huge push [00:20:00] to try to bar queer and trans folks from the classroom, from having any contact with children.

Just this suspicion and anger, which often would lead to violence of queer and trans folks in any relationship to children. You know, one of the biggest things that we were responding to is really breaking those myths around who sexually abuses children, and really pushing against the criminalization of queerness and transness that was very much leading to violence. And really getting to not only the very real data that is out there, but also breaking those inherent stereotypes that, you know, try to tell us that being queer, being trans, it’s a sin. And, you know, these people are dangerous and criminals. And at the same time, we were also being [00:21:00] flooded with calls of folks who were experiencing child sexual abuse in their families and in their communities.

And so we were kind of juggling both of those things of like, and folks not, you know, wanting to go to the police. And some of these were instances that were happening in real time, right? Right at the, at the moment. But some of these also were kind of historical cases where folks were like, I just discovered this huge line of folks being sexually abused in my family by my grandfather. So we were trying to respond, or were responding to both I think of those things at the same time.

And connected to that, the idea then that like that would make people queer. Right? Or trans, that somehow if you were sexually abused, that was why you were queer or trans. And so this further kind of demonization of queer and trans folks on [00:22:00] all these different levels of like, not only are you queer or trans because you were sexually abused, but now you’re going to go on to sexually abuse other children, and therefore we need to criminalize you in all these ways. It means that we have the right to enact violence on you in all these different ways. You know, you’re lying to us about who you are.

Yeah, it was just even thinking about how intense at the time that was, and all of those things that we were responding to. Like very real pain and violence and hurt and confusion and, you know, trying to bring some, some clarity and some, some hope and some healing and some repair. And some very real information about child sexual abuse to folks that often really didn’t want to hear it.

Like they had their ideas about who sexually abuses children, and they didn’t [00:23:00] want to hear that the majority of folks who experience child sexual abuse experience that not by some queer trans stranger out there, but actually in their homes and by people that they know, and that it has nothing to do with being queer and trans.

Morgan: Thank you Micah. I am gratefully and painfully reminded of the intense pathologization and criminalization and just sitting with right now how that has really taken root as such the cornerstone right now of this white nationalist right wing agenda that is fueling so much violence now in our political system.

And just thinking about how like that similar moment in the 70’s too of like this idea of queer and trans people as sexual predators. Somehow the ways in which TERFs [trans-exclusionary radical feminists] have taken that up to be that somehow trans women are predatorial against non-trans women. You know, like, and then using that to justify violence.

Deana: Hearing from the two of you, what was going on is huge. And it’s really [00:24:00] hitting me in ways that reading about this work wouldn’t. So I appreciate that you’re sharing these difficult stories. Thinking back during those times, are there certain success stories that do pop out to you that you can say, you know, that was, that was successful.

I mean, of course, success is not black and white, you know, I’m not saying it’s a binary. But were there certain moments or stories that you can remember that you can say, “oh yeah, that was successful.”

Morgan: I remember a couple convenings during that period that felt like huge victories and that felt like places where people were cross pollinating and learning from one another and making explicit or experimenting with frames and ideas and concepts for how to reorganize our resistance and amplify and strengthen our resistance.

And one of those convenings was in 2007 called Transforming Justice, which was one of the first gatherings of formerly incarcerated trans people [00:25:00] and their allies and advocates and organizers. And it was at City College in San Francisco. And I was grateful to get to be part of the organizing team. And it was a real collaborative effort of so many, so many people and organizations and long-term prison abolitionists and, and long-term activists. As well as people who were in like LGBTQ orgs who wanted a more radical agenda and, and there was only about maybe 200 of us that came together for two days in 2007.

It felt like its own kind of victory. We were getting to speak back again to what priorities had been set for our, our movement. And then in 2008 there was the Critical Resistance 10 conference, the 10th anniversary of the first Critical Resistance conference. And that felt like another opportunity where people were coming together and bringing these threads together around the need for transformative justice, the need to continue popularizing prison abolition.

And in that convening, and I think in general in the history of prison, abolition Critical Resistance, the [00:26:00] role of the radical imagination was so centered. We have to imagine beyond what we can see and beyond what we have been told is inevitable, is permanent, is ahistorical. You know, we have to imagine beyond it. And obviously the central role of Black feminism in making prison abolition possible.

And then the US Social Forum in, in 2010 in Detroit felt like yet again another space where we were all coming together in different ways to try to popularize these ideas and say that both prison abolition and transformative justice aren’t separate, marginal kind of parts of the work, but are actually integrated in, in all struggles, ’cause all struggles were organizing people who are constantly facing violence.

And the frame of abolition, like Ruthie Gilmore talks about, “we need to change everything.” So abolition is not just about those working on prisons and police, but it’s about reorganizing our entire society that is organized around prisons and police and carcerality and [00:27:00] criminalization.

And same with transformative justice, that all of us get to build these skills. All of us get to recover skills, skills within ourselves, strengthen skills within ourselves that are about changing how we are with one another. Making how we are with one another more and more fulfilling, and more and more satisfying and less and less harmful, and more and more in line with our values.

So those three convenings did feel like victories in some way of like bringing people together and staging conversations and laying some groundwork for work that would follow.

Micah: It’s so interesting that you talked about convenings because I agree. But I think for us, at generationFIVE or, you know, at least for me personally, I think actually the very first Social Forum in 2007 in Atlanta was probably the place that I would say we experienced something that felt like our very first success. You know, we looked at it as like the formal introduction of transformative justice. With more of like a language [00:28:00] and principles and, you know, a theory and a practice. And, you know, we released our document Towards Transformative Justice at that initial Social Forum.

So it was really exciting to kind of go into this movement space to, you know, really like formally present of like, look, here’s this work organizations and collaboratives have been working on together, and what do you think? You know, like, here’s this other way to really think about accountability.

Also, for us as an organization, generationFIVE, it was also an opportunity for us to say, and here’s why child sexual abuse matters to the broader movement. Here’s why child sexual abuse isn’t just some kind of side psychology issue, or, you know, social work issue. Like why child sexual abuse actually matters to our movements and why we need to understand how child sexual abuse intersects [00:29:00] with all of the work that we’re doing. It intersects with racial justice, intersects with economic justice, inter.. intersects with prison abolition.

And I think for us that was a huge moment, right, to really be able to articulate the need for our movements to really understand how child sexual abuse interacts [with] our broader movement work, why it’s important. And then to also have this way of responding through transformative justice, not only to child sexual abuse and sexual violence, but also to all of the violence that we are pushing back against and trying to work to stop and dismantle more broadly.

So I think that very first Social Forum 2007 in Atlanta was a huge success and kind of moment of like, oh wow, look like we could actually maybe like, do this. And then I think I would agree with Morgan that [00:30:00] 2010, the Social Forum in Detroit was another moment. You know, it had been like three years by that time, and so there had been some time, you know, for folks to grapple with it, to explore it, to use it. One of the moments of success, particularly in that Social Forum, was the integration and kind of forwarding an introduction of “healing justice” as this way of like, okay, we’ve got transformative justice that’s really looking at accountability, and now we have “healing justice,” which is really looking at how can we have accountability and healing and repair and like outside of systems that are actually not built for accountability or healing and are led by us, led by us on the ground.

And really both of these things looking at transforming our context and our conditions, bringing back our [00:31:00] ancestral practices. And I think definitely for me, at least, that was kind of the magic of 2010 is like, okay, now we’ve named this healing piece as well. We’ve named the accountability piece. Now we’ve really like named and articulated this healing piece, and they both go together. They both work together. We can’t have one without the other, right? Like we can’t have accountability without healing, and we can’t have healing without accountability. So I think those two moments were really profound.

And then I think the last moment that I really think about is the launch of our “study into action” process, which I think we did, I don’t know, maybe 2010, starting 2009. But it really, for us was this, you know, this moment of like bringing folks from different places of work, you know, together to really collaborate with [00:32:00] one another on how do we put all of this into action?

What do we need to learn? What do we need to study? How do we translate this into our locations of work? You know, so we had teachers, we had, you know, social workers, we had folks [doing social] justice work, folks doing environmental justice work, folks doing gender work. Some who considered themselves, you know, activists or movement people, some of them who really didn’t, really coming together for a single purpose of moving something out of theory into actual practice and action on the ground. And what does that look like in different locations and contexts? And that was a really powerful project. I think that was a success as well.

Morgan: Just to build on what you’re saying about like the role of study that was being experimented with in study into action, I feel like that …one other victory of that time that’s related to what you’re saying, Micah, is like…[00:33:00] just in an embrace of the terms of experimentation and improvisation and practice rather than destination and perfection. I remember at CUAV we had a series called The Safety Lab, which was really inspired by the Audre Lorde Project and their Safe Outside the System. I remember we went to one of their convenings where they were talking about role playing and using and using theater of the oppressed to role play how would you intervene in the situation on the subway? And we kind of adapted that over in San Francisco where we would come together in these like safety labs and talk about different situations and kind of use theater of the oppressed, and use different, different tools to kind of role play and get our imaginations going.

And uh, I remember we got to do that workshop at the, at the Social Forum in 2010 with Prentis Hemphill and Carolina Morales and Maisha Johnson, who were all on staff or members of CUAV at that time. And I feel like the role of STOP StoryTelling & Organizing Project [00:34:00] so much set that tone, too, of like this kind of affirming…We can start small. We can build on what we know. We can experiment. We can practice rather than internalizing the feeling that we have to have all the answers right away, which inevitably we… we will not meet. And then, then we will sort of feel like we’ve failed over and over again.

And the state has done that to us. The state generationally has convinced us we don’t know anything about safety. We don’t know anything about how to deal with violence. They are the only ones who know how to deal with it. That…that you have to be experts. And so we’re de-internalizing that message. And like Micah was saying around healing justice, transformative justice, like remembering what we maybe already know or what we long to practice.

And I feel like one of the victories of that time was like saying, yeah, we, we don’t know all the answers, and that’s okay.

Micah: I would definitely agree with that. I remember Safety Lab and loving that. And what I want to just [00:35:00] kind of echo is one of the last things you said is this idea of remembering, right?

And I feel like that is what really drove a lot of our work is, is this idea that like we don’t know all the answers, and we know some things. How do we also remember what’s been lost or what’s been taken from us, and bring those things back. And also, you know, the freedom to experiment and to not be in this capitalist white supremacist narrative of – you must know everything, you must do it right all the time, and you must produce, right?

Like how, how many things can you, can you produce? Right? Which often, you know, we get caught in, especially being in nonprofit organizations that are dependent, you know, on grants and, you know, grant results or whatever, but, you know, just having this, this freedom to practice and to play in some ways, which is so [00:36:00] important of like even, you know, what we’re talking about is like, is violence right? You know, horrific things, but how can we still stay connected to joy and to play and to experimentation and remembering?

You know, there were so many things about that time that were… were so hard. And also, there were so many things about that time that were just so great and wonderful and inspiring. You know, we really held each other in the hard times and practiced, you know, resilience.

Deana: The successes you shared were super powerful, and I really appreciate being taken back along that kind of memory lane and the reminder that there is joy in this work, even when it’s hard. I also wanna talk about the challenges that you might have experienced or you did experience in the work that you were doing.

So, what [00:37:00] are some challenges that jump out to you, that you remember or that stick out to you, and how did those challenges grow your work?

Micah: So I think one of the main challenges for us at generationFIVE in particular was, was funding. As a nonprofit, funding is a challenge for, you know, most organizations, but I think for us it was a particular challenge because of the way that we were approaching our work.

You know, our main focus was in ending child sexual abuse. And if we were doing that work and approaching it kind of in the traditional ways, so focusing on, you know, criminality and longer sentencing laws and you know, stranger danger and those sorts of things, then I think we probably wouldn’t have had the challenges that we had around funding.

But because we were working around ending [00:38:00] child sexual abuse outside of the police, and also by understanding the connections to systems of oppression, the ways that we really were approaching child sexual abuse, and this reframing of like, you know, accountability happens in connection – not in prisons.

You know, we need to understand how trauma impacts our, our families and get passed down and, you know, how do those things connect to child sexual abuse? Often we would talk to funders and they would just be like, we don’t even understand what you’re talking about, and there’s no way that we could possibly fund you for this work because we don’t understand it.

It doesn’t fit into any of our priority goals or whatever. We don’t even know how to measure what it is that you’re doing. So then, you know, how do we know if it’s a success? You know, there were, there were always these [00:39:00] kinds of questions that we would get, and blocks that we would have in looking for funding that, you know, and, and because we weren’t doing service provision, as well, that was the other piece.

Because I spent, also spent some time as our development director trying to meet with funders, trying to meet with grant folks, like they could not conceive of doing child sexual abuse work in the ways that we were trying to do it. So that really impacted us a lot, of trying to run the organization day to day, you know, pay people.

We experienced another challenge kind of inside of movement spaces of, where people being like, why are you trying to get us to talk about child sexual abuse? Like, this has nothing to do with racial violence, or, you know. We’re organizing around environmental justice, like we don’t understand why you want to talk about child sexual abuse.

Like this has nothing… [00:40:00] like that’s a service provision issue. Or, you know, talk to the social workers. Or you know, whatever. It took a while for comrades in some of the, the movement spaces to really understand why child sexual abuse was important to understand, important to work on. An important kind of location connected to other types of movement work. Right? And how it actually wasn’t separate. It wasn’t separate at all.

Morgan: Yeah. Thank you, Micah. I also started at CUAV as a development person, so I, I can really relate to funding struggles and having to find new donors or re-educate donors. And I, I also feel like one of the things that was also happening in that time period was sort of like a deeper learning about grassroots fundraising, understanding it as a movement organizing strategy. As a strategy to organize people as a way to push back on some of the strictures that both foundations and the state put on our work.

And, in fact, CUAV’s reorganization and, and shift [00:41:00] happened at the same time. And also through a, a big loss of funding when California eliminated a huge chunk of its domestic violence funding – at the same time expanding prisons.

I feel like so much of our work in organizing is trying to seize crisis and not let shock doctrine take over and actually let liberation doctrine like take over and try to move with various crises, whether that’s loss of funding or certain kinds of repression, and say, how do we keep pivoting towards expansive justice-oriented ideas and…

Yeah, I just really also wanna say like the names of who was in the collective in that moment of like Pablo Espinoza and Carolina Morales and Prentis Hemphill and Norio Umezu and Tamara D’Costa, and there were so many others who were members and board members and supporters. So definitely just echoing that challenge around funding.

And then the other two challenges that come to mind is the conditions of gentrification in San Francisco [00:42:00] and the complete divestment from social services, abandonment of houseless people, criminalization of houseless people, gentrification, taking over areas like the Tenderloin, where a lot of SROs are, and a lot of our members lived.

And like just an affirmation of what our movements have always been saying that safety comes through strong communities. It comes through well-resourced communities. It comes through having housing and healthcare and affirming education and these kinds of resources, and that when we have those, safety becomes a whole other conversation.

And so in some ways, like the fact that there was this housing crisis and that one of the responses in gentrification is also to add policing. That was part of the challenges that we were… that we were navigating of saying people would come to us experiencing violence, and what they also were needing was housing, uh, safe housing. And just the ways in which the responsibilities of the state have been kind of outsourced to various nonprofit organizations to kind of make up for the crises created by [00:43:00] capitalism and created by the state. So I think that’s another challenge.

And then the third challenge that comes to mind is, which again, is like inseparable from the opportunities we make out of crisis, which is pinkwashing. Which is also during this time, this kind of accelerated effort on behalf of the Israeli government to paint itself as a LGBT safe haven. And to pinkwash its colonial apartheid occupation since 1948 of Palestine and Palestinians as somehow a progressive project. And there was a intentional effort during those years that we’re talking about to put out a lot of propaganda and try to infiltrate a lot of our movement spaces with the idea that Israel is, is anything but an apartheid colonial project. And specifically using gay and queer people and trans people as kind of as if it has anything positive to offer and also as if queer and trans Palestinians don’t exist.

So I think that was also another influence that as a movement, we also were able to push back on. I remember, you know, there was just a [00:44:00] lot of campaigns that were popping up around the country in the Bay Area, certainly at the US Social Forum. In Seattle, where pink washing events were being staged where organizations like Stand With Us, were masquerading as social justice organizations that were actually just defending Israeli apartheid, trying to paint it with every rainbow flag. And so during that time, it’s impossible to separate the people we’re talking about from also Palestine solidarity and all the international solidarity movements that we’re all a part of.

And we were pushing back in that moment out of the efforts that we still see and are, in some ways stronger than ever, to repress Palestinian resistance and Palestinian movements and Palestine solidarity. And that’s also tied to funding which we know, we know like service organizations would, there’s plenty of examples, but they would, their funding would get pulled if they said something about Palestine.

So all these things are kind of connected, and I wanna emphasize all of them. Our movement legacy teaches us that we, we don’t get to pretend the crisis isn’t there, and we don’t get to pretend the challenge [00:45:00] isn’t there, but we do get to try our best to respond and transform the moment towards liberation instead of using it as, you know, more moments for shock doctrine.

Deana: That is a beautiful segue to my next question as we wrap up the conversation. I mean, you’ve shared so many important moments that we can and should learn from. And you know that we have new folks coming into this work. What are some things that you would want new organizers to know?

Morgan: I don’t know what I want them to know, but what I want them to feel is that they have so many people at their backs who they know and don’t know.

And there are plenty to learn about, and some of you will just never know about. People who’ve been doing the quiet work for years and years and years to make possible what we now understand as normal. You know, even like the incredible infrastructure around supporting people who are locked up. The incredible infrastructure and wisdom and skills around supporting [00:46:00] survivors of violence, of all kinds.

There is a river of people behind you. A river of people behind you, who relate to the challenges you are facing. Also did not know the answers. And also, like Micah said, knew something and had convictions and so knew they had to try. And so what I want, what I hope that new people in this work can feel is that you are not the first and you will not be the last.

May you feel some supportive hands at your back saying, “in moments of impossibility and despair, keep going.” Try to be kind to each other and to [be] kind to yourself and to not minimize what we’re up against, but also to not minimize the power of like our human drive towards life. We just keep moving towards life.

Where there is oppression, there is resistance. Where there is oppression, there is joy. Like we just keep moving towards life. And so that’s not to romanticize any of the challenges that newer people are gonna face, but just to say you’re in a lineage of people who are holding that, those tensions and contradictions who are at your back.

Maybe one more thing would be, what I hope [00:47:00] you know is that, like Micah said, that quality of joy and play is, is indispensable and is one of our most profound political weapons. Mohammad el-Kurd, Palestinian activist, talks about how laughter is dignifying and like we don’t have to see the domain of play to the powers that be.

They’re a part of our inheritance and part of how we invite people into a world we can’t yet see. So just to affirm all the ways in which we can inhabit playfulness and joy. It’s not a contradiction with grief and despair and rage. It’s not, it lives right alongside of it, and all of it is about being human. And that’s our work is to get to be human together.

Micah: I love that, Morgan. I think where I wanna pick up from where you left is with the piece around joy. To me, joy is resistance. Right? And it’s, it’s definitely one of the things that I’ve been kind of remembering and witnessing and appreciating in the Palestine liberation work, right? Is just, yeah, joy is resistance. [00:48:00]

And so I think to me, that is one of the biggest things that I want new organizers to know or to remember and to practice is joy and play and, and fun. And, you know, I, I’ve been making these kind of wound, medicine, purpose triangles. It’s a, a practice that I was, I was taught and have been kind of playing with that, especially in these times.

And, and there’s one, you know, that I have for myself where the wound is grief, the medicine is joy, and the purpose is love. Right? And so when I look at that in the context of, you know, of our, our movement work, especially when things feel very hard or very overwhelming or, you know, I’m in those places of like, is what I’m even doing, does it matter?

I can look at this triangle and, you know, and, and feel the grief, right? As, as wound. And remember that the medicine for that is [00:49:00] joy. And so how do I engage in joy? And the ultimate purpose is love, right? And just reminding ourselves that we do all of this. We go through all these challenges and hardships. We feel all the grief because we love. We love so hard. We love our people, and that is really the purpose of all of this.

And so I just want to also remind new organizers to remember that, to to tap into that love, right? The love of your people, which brings you, you know, to this work – keeps you in it, even when it seems impossible – to remember to ground in that love, right?

And then I guess, you know, the other thing I would want folks to… to know is like Morgan said, you have so many folks at your back. And, part of your work now is the moving forward, right? Staying connected to [00:50:00] what’s at your back, but moving forward. And we’re now in a time, especially as you know, things are falling apart around us as the empire is slowly dying.

As you know, capitalism is in its last stages and gasping for, for breath. Now is the time of imagination. Now is the time of dreaming. And we need you to imagine and to dream what comes next into being. And from there is how we build it, right?

So yes, stay connected to what’s been, stay connected to those folks who stand at your back and have your back and the legacies, multiple legacies that you come from, and then look to the future, imagine, and dream.

Because that’s what we need right now.

Morgan: I’m so grateful for your, your, the visionary way in which you just laid that out for us, and that you’re bringing us back to love. [00:51:00] And that love is not about being perfect, and not about needing each other to be perfect. And that is one saying that Dean Spade, who has been involved with this work for so many years shared with me, that I’m sure he learned from somebody else. That we are imperfect people doing imperfect work. And that if you are starting out in this work, you do not need to be perfect and you, you won’t get perfect. And we don’t need to have perfection be our standard ’cause it will, it’s not the horizon for us.

And that part of… part of really rooting this radical love that I think you’re talking about, Micah, is, is embracing our humanity and our imperfect, and our imperfectness and not waiting for perfect versions of ourselves, but these are the versions that we have now.

Deana: All of that was so beautiful and thank you both so much for that. Like it really spoke to me during this time. It was fucking amazing.

Thanks to our brilliant guests. We are so grateful for the role and movement they continue to play. We also wanna thank the [00:52:00] amazing queer and trans organizers who are making this world a better place for all of us every single day.

As always, I encourage you to take the lessons you learned today and keep practicing.

Have you facilitated a process using community accountability tools or strategies? We wanna hear your stories. Creative Interventions and Just Practice Collaborative wanna share new stories from people who are taking action to end interpersonal violence without the use of police or carceral systems. Find the link in our show notes to learn more.

Stories for Power is presented by Creative Interventions and Just Practice Collaborative. Executive produced by Mimi Kim, Shira Hassan and Rachel Caidor. Produced by Emergence Media. Audio editing and mixing by Joe Namy and iLL Weaver. Music composed by Scale Hands and L05 of Complex Movements in collaboration with Ahya Simone.

Stay tuned for more episodes of the Stories For Power podcast. Check out our show [00:53:00] notes and go to StoriesforPower.org to learn more.